So You Think You Can Dance Laura Roderman

Norma Beecroft, Electronic Pioneer

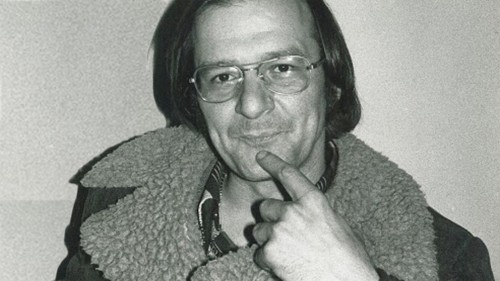

Canadian composer Norma Beecroft (b. 1934) recently released her book, Conversations with Post World War II Pioneers of Electronic Music, containing an insightful and revealing collection of interviews that explore the history of electronic music around the world. The book, originally published as an e-book, contains transcriptions of her interviews with many of the principal innovators who shaped electronic music from its earliest days. Beecroft, of course, is herself one of the pioneers of electronic music.

Canadian composer Norma Beecroft (b. 1934) recently released her book, Conversations with Post World War II Pioneers of Electronic Music, containing an insightful and revealing collection of interviews that explore the history of electronic music around the world. The book, originally published as an e-book, contains transcriptions of her interviews with many of the principal innovators who shaped electronic music from its earliest days. Beecroft, of course, is herself one of the pioneers of electronic music.

Her creative life closely mirrors the appearance and development of what was, in the mid-20th century, the newest musical medium. Given that she was also a prolific broadcaster and a maker of radio documentaries about contemporary composers of her day, it should be no surprise that she decided, in 1977, to embark on this landmark series of interviews with her fellow electronic music pioneers.

The list of the composers included in Beecroft's book is comprehensive, reading like a who's who of early electronic music. Among the 23 interviews, prominent names such as Luciano Berio, John Cage, Pierre Schaeffer, Karlheinz Stockhausen and Iannis Xenakis jump out of the group. Max Matthews, the so-called "father of computer music" is there. And there are important Canadian innovators as well, such as Bill Buxton, Gustav Ciamaga, James Montgomery and Barry Truax. Each interview is framed with a carefully drawn profile of her subject, intricately and accurately placing each into historical context.

The 400-plus-page book also contains an extensive preface, in which Beecroft introduces the overall subject of the relationship between music and technology, which is broadly relevant to her topic. She also details highlights of her own career, creating historical markers in the process, that show her creative work in parallel with her interview subjects. She describes herself as, "the second of five offspring of a father who was an inventor, Julian Beecroft (1907–2007) and one of his main interests was acoustics and sound, which he began investigating when he was very young." She touches on her early composition lessons with John Weinzweig (1913–2006), interspersed with her other career activities, including her work with CBC Television in the 1950s, a time when TV was the newest of the broadcast media. It was also a period of her life when she travelled extensively, to both the United States and to Europe, meeting numerous composers, conductors and performers in the process. These acquaintances helped her in the development of the many phases of her career: composer, broadcaster and arts administrator (this latter role as co-director – with Robert Aitken – of Toronto's New Music Concerts, from 1971 to 1989). And a great many of these colleagues found their way into her collection of interviews.

Beecroft writes: "It was inevitable that I would join those questioning the present and future value of this new technology to music, this fascinating interaction between the fields of science and the humanities. And so, in 1977, I began my investigations into exploring music's relationship to technology through the voices of some of the world's foremost creative musical minds." She concludes her preface with the notion: "It is generally agreed that the field of electronic music began in Paris, France, in the studios of the French Radio, then experiments in this new domain were being conducted at Columbia University in New York, and at the West German Radio in Cologne. Accordingly, I have ordered my collection of interviews in the same manner, beginning in France, and then moving to the United States and Germany, then followed with important work by Luciano Berio (1925–2003) and Bruno Maderna (1920–1973) at the Italian Radio in Milan, and concluding this volume with the interviews in Canada." At the same time, she notes: "All these activities were mushrooming around the same period of time, in the years immediately following World War II, so the order is essentially inconsequential."

Beecroft began organizing her enterprise in 1977, in a series of letters to her intended subjects in Europe. She told me she was confident in positive responses from the composers since she was known to them, and that they trusted her knowledge of the subject. She was by this time acknowledged not only as a composer, but as a highly skilled broadcaster, and she had easy access to all her subjects. She told me that Iannis Xenakis (1922–2001), for example, said: "One thing I like about you is your determination." Her travels took her first to Cologne, Berlin, Köthen, then Paris, London, and Utrecht. Additional interviews were scheduled in the United States, and back home in her Toronto studio, when possible.

Beecroft began organizing her enterprise in 1977, in a series of letters to her intended subjects in Europe. She told me she was confident in positive responses from the composers since she was known to them, and that they trusted her knowledge of the subject. She was by this time acknowledged not only as a composer, but as a highly skilled broadcaster, and she had easy access to all her subjects. She told me that Iannis Xenakis (1922–2001), for example, said: "One thing I like about you is your determination." Her travels took her first to Cologne, Berlin, Köthen, then Paris, London, and Utrecht. Additional interviews were scheduled in the United States, and back home in her Toronto studio, when possible.

The results of all these interviews were highly rewarding, and revealed great amounts of both historical and personal details. Beecroft's subjects opened up to her highly focused line of questioning, delving into the recent past, to a time when they were all drawn to the artistic and technical challenges of this new musical medium. In the very first interview, for example, with Pierre Schaeffer (1910–1995), inventor of the concept of musique concrète using recorded sounds, and who founded Le Club d'Essai in 1942 and the Groupe de Recherche Musicales in 1958 in Paris, it's immediately clear that Schaeffer's focus is primarily on research and engineering. He refers to clashes in methodology with Pierre Boulez (1925–2016), Karlheinz Stockhausen (1928–2007) and Iannis Xenakis, and confesses: "I hate dodecaphonic music, and I often say that the Austrians shot music with 12 bullets, they killed it for a long time." This was a somewhat surprising revelation for me, but is typical of the sort of candid views Beecroft's colleagues were willing to share with her.

In the Stockhausen interview, by contrast, we find the other side of the argument. "In Paris I became involved in the musique concrète that was at that time just beginning to develop. Boulez made me listen to a very few, very short studies, and immediately I was interested in trying myself to synthesize sound, and to get away from the treatment of recorded sound." Stockhausen went on to mention his collaboration with Belgian composer Karel Goeyvaerts, who had suggested a technique of combining pure sine waves to synthesize timbres: "I have to say that the friendship with this Belgian composer, and the exchange of letters with him, was a very important reason why I made these first experiments, because we were both thinking that it would be a marvellous thing if we could synthesize timbres. The general idea of timbre composition was in the air from texts of Schoenberg."

Goeyvaerts recalled in his interview: "I never thought that pure sine waves could be heard. And suddenly I found that they existed with an electronic generator, so I wrote to Stockhausen and said, now we can go ahead." He added: "When Stockhausen made the Study No. 1 and when I made my piece in 1953, I must say we considered at last we could come to a pure structure." It was also in this year that the term "electronic music" was coined by Dr. Herbert Eimert (1897–1972) at the studio of the Cologne Radio.

Historical turning points such as these appear often throughout Beecroft's Conversations with Post World War II Pioneers of Electronic Music. But as important as such details are, the personal notes of the composers are possibly the more interesting aspect. An example is in the interview with American composer Otto Luening (1900–1996), who studied with composer and virtuoso pianist, Ferruccio Busoni (1866–1924), and was friends with composer Edgard Varèse (1883–1965). Luening said, of Busoni: "The essence of music, the inner core of music was to him still a mystery and he was like Schopenhauer in that, who I believe said somewhere if we knew the mystery and relationships of music, we would know the mystery and relationships of the whole universe." And of Varèse, Luening said: "We immediately hit it off. Not only did I have great affection for him, and liked him very much personally, but we had this Busoni tie." He mentioned the various stylistic groups of American composers current and pointed out: "Varèse and I were on this other line, we were really free wheelers, you know, and while we had a very strong aesthetic, it was not organized, there was no movement or anything, and we never wanted one. We used to talk together and so gradually we fell into a group of friends, that were very interesting and all kind of iconoclasts."

These personal snapshots were entirely a part of Beecroft's focus and plan for her project. In a letter to Stockhausen after the first edits were finished, she told him: "The publication is not intended to be a scholarly document on technical matters but an insight into the internal world of the composer and sociological forces that helped shape the person." She projected to him that, "I am sure this modest document will help fill a void when it comes to musical matters in the latter half of this century." The book is available through the Canadian Music Centre, 20 St. Joseph Street, Toronto, and can also be ordered online. The details can be found here: musiccentre.ca/node/155113.

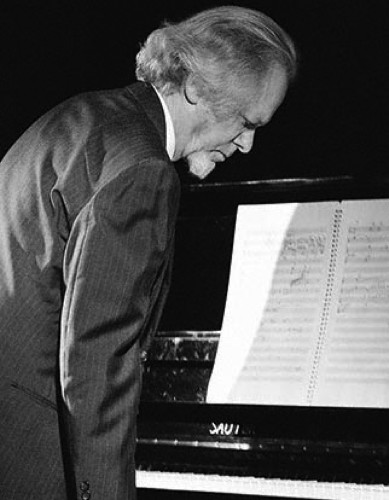

Norma Beecroft continues to compose. Montreal composer-pianist Bruce Mather invited her to create a work for his Carrillo piano, an instrument with 96 notes to the octave, which is to say, it's tuned in 16ths of tones. Beecroft's new composition will have its world premiere on March 11 at 7:30 at the Salle de concert of the Conservatoire de musique de Montreal, 4750 avenue Henri-Julien. It's a work for solo Carrillo piano with digital soundtracks. Beecroft wrote: "Written for my friend and colleague Bruce Mather, this piece posed challenges that I could not resist. Having worked in analogue studios for most of my career, I determined to try my hand at composing using digital software only. The Carrillo piano was another challenge, as the entire piano keyboard consists of only one octave of sound. Training my ears to hear the microtones was a new problem, as was a system of notation for the performer. Herewith – my modest attempt at combining the two elements!" She explains further that the work's design, "finds its analogy in nature, with the opening and closing of a flower. The one octave is divided in half and opens up slowly to create ever-widening intervals. And the flower slowly ends its fragile existence in a retrograde movement."

Norma Beecroft continues to compose. Montreal composer-pianist Bruce Mather invited her to create a work for his Carrillo piano, an instrument with 96 notes to the octave, which is to say, it's tuned in 16ths of tones. Beecroft's new composition will have its world premiere on March 11 at 7:30 at the Salle de concert of the Conservatoire de musique de Montreal, 4750 avenue Henri-Julien. It's a work for solo Carrillo piano with digital soundtracks. Beecroft wrote: "Written for my friend and colleague Bruce Mather, this piece posed challenges that I could not resist. Having worked in analogue studios for most of my career, I determined to try my hand at composing using digital software only. The Carrillo piano was another challenge, as the entire piano keyboard consists of only one octave of sound. Training my ears to hear the microtones was a new problem, as was a system of notation for the performer. Herewith – my modest attempt at combining the two elements!" She explains further that the work's design, "finds its analogy in nature, with the opening and closing of a flower. The one octave is divided in half and opens up slowly to create ever-widening intervals. And the flower slowly ends its fragile existence in a retrograde movement."

Also in Montreal in March, a special dramatic concert presentation titled "Between Composers: Correspondence of Norma Beecroft and Harry Somers, 1955–1960" will take place at the Tanna Schulich Hall of McGill University on March 22 at 7:30pm. Composer and McGill music professor Brian Cherney conceived the presentation, and he describes the idea:

Also in Montreal in March, a special dramatic concert presentation titled "Between Composers: Correspondence of Norma Beecroft and Harry Somers, 1955–1960" will take place at the Tanna Schulich Hall of McGill University on March 22 at 7:30pm. Composer and McGill music professor Brian Cherney conceived the presentation, and he describes the idea:

"From 1955 until early in 1960, Norma Beecroft and Harry Somers were involved in a romantic relationship. In the fall of 1959, Norma went to Rome to study composition with Goffredo Petrassi. While there, she also studied flute with Severino Gazzelloni, the renowned flutist for whom many composers such as Berio wrote important new works for flute. During the last months of 1959 and early 1960, Somers and Beecroft exchanged nearly 200 letters, providing considerable information about their evolving relationship, what music they were writing, various compositional concerns, and the people they were meeting (in Toronto and in Rome). As well, Norma Beecroft's letters describe her struggle to gain the confidence to study composition but also to finally reject a permanent 'domestic' relationship with Harry Somers, in other words, to devote herself entirely to composition. Thus the letters give us a fairly detailed portrait of that period in Canadian composition (of concert music): their compositional concerns, problems of financial support, thoughts about the state of the arts in Canada, and so on.

"In the concert being presented at McGill University on March 22, I have chosen significant excerpts from these letters and these will be read by two people, interspersed with music by each of the composers, chiefly, the String Quartet No.3 (1959) by Somers, dedicated to Norma Beecroft, and the film Saguenay, for which Somers wrote the music in early 1960 (and described in detail in the letters) and the Amplified String Quartet with Tape by Beecroft, written in the 1990s."

Norma Beecroft will take part in both these Montreal events.

Returning briefly to the topic of the history of electronic music, I'm happy to announce that on March 8, a 1977 vintage recording by the Canadian Electronic Ensemble (CEE) will be released on the Artoffact record label. The CEE is a performing ensemble that I helped to establish in the early 1970s, and which continues to function even now, nearly 50 years later. This vintage re-release is a remastered version of the debut album by the CEE, originally released on an LP on the Music Gallery Editions label. By coincidence, the music contained on the album was all composed and performed at roughly the same period of time as Beecroft was travelling the world recording her interviews. The CEE's founding quartet of David Grimes, the late Larry Lake, David Jaeger (aka me) and James Montgomery are the performers, together with a guest appearance by the late pianist Karen Kieser. The album is available as both a CD and in digital formats on Bandcamp: thecee.bandcamp.com.

David Jaeger is a composer, producer and broadcaster based in Toronto.

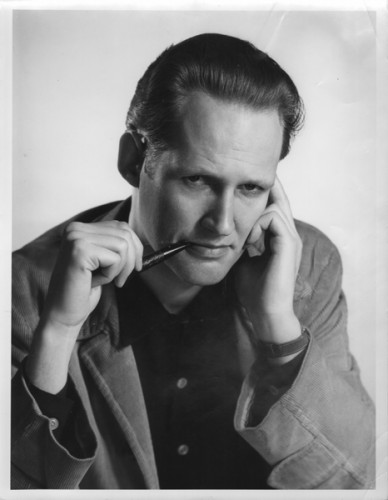

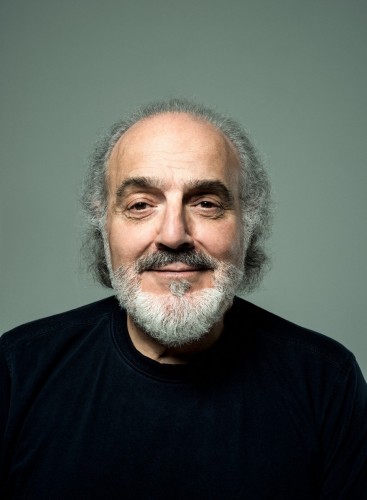

Alex Pauk's Esprit: Wave After Wave

![]()

There's a great Alex Pauk story that filmmaker Don McKellar once told me, about the final stages in the production of McKellar's 1998 feature film Last Night, for which Pauk and composer Alexina Louie, partners in life and in art, composed the score. (I can't swear to when McKellar told me the story, except that, evidently, it must have been sometime after 1998.) Whenever it was, it's had time to ripen with age and retelling, so I will trust all parties concerned to forgive the parts I am no longer getting quite right.

There's a great Alex Pauk story that filmmaker Don McKellar once told me, about the final stages in the production of McKellar's 1998 feature film Last Night, for which Pauk and composer Alexina Louie, partners in life and in art, composed the score. (I can't swear to when McKellar told me the story, except that, evidently, it must have been sometime after 1998.) Whenever it was, it's had time to ripen with age and retelling, so I will trust all parties concerned to forgive the parts I am no longer getting quite right.

The way I remember it, Pauk and Louie contacted McKellar to say that the score was complete and ready for him to hear, and that an appointment "three sharp" was set for the given date and the appointed place. "Three sharp" was however not necessarily a musical term McKellar was familiar with, back in the day, so when he strolled up, Pauk was already pacing. "You're late!" was the greeting, in a tone more stressed than McKellar thought the situation warranted.

The way I remember it, Pauk and Louie contacted McKellar to say that the score was complete and ready for him to hear, and that an appointment "three sharp" was set for the given date and the appointed place. "Three sharp" was however not necessarily a musical term McKellar was familiar with, back in the day, so when he strolled up, Pauk was already pacing. "You're late!" was the greeting, in a tone more stressed than McKellar thought the situation warranted.

McKellar wandered in, expecting to find himself with headphones on, listening to a tape or piano reduction or something … "and than they open the door to the room, and there's a whole symphony orchestra there, waiting to do their thing. It felt for a moment as if I must have died and gone to Hollywood."

As implausible as that moment in time must have felt, on a larger scale the fact that Esprit, the orchestra in question, is still alive and ticking after 35 years, is almost as implausible; and a story worth telling in its own right.

Esprit at 35

Esprit at 35

In the middle of this significant anniversary year for Canada's only full-sized orchestra completely devoted to performing and promoting new orchestral works, we could have chosen to approach this story in a few different ways:

There's the way this season's four mainstage Koerner Hall concerts (there's still one to come, on March 24) reflect the philosophy (and formula) that has given the orchestra its remarkable consistency and astonishing staying power. "My programming is something I always take great care with and pride in," Pauk says. "Making the programs so that they flow, so that it's not all one thing. I mean if you did all hard-edged European music all the time, it wouldn't go over well, so there's an ebb and flow in a concert, variety …"

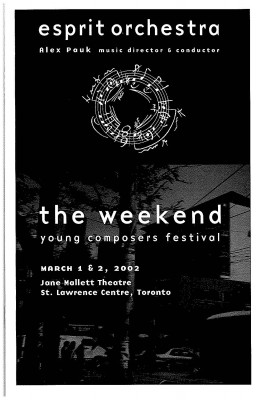

Or there was the orchestra's decisive move from the cramped confines of the Jane Mallett Theatre (the stage used to look like an overloaded life raft for some of the larger works they performed there) to Koerner Hall (twice the capacity) in the very first year Koerner opened. "We're both celebrating our tenth anniversaries there!" Alex Pauk says with a grin. "You could overpower the Jane Mallett fairly easily" I observe. "Your Xenakis certainly did, when was that, in 2006? I think that was actually the start of the renovations there … your knocking every bit of loose plaster off the walls with the sound." He laughs. "We certainly did. But you know, we, the tenants had a lot of ideas for those renovations, for the hall itself. And what did we get?

A renovated lobby."

Or there's the whole subject of what it takes to keep implausible enterprises afloat (a topic on which we agree to indulge in no more than a few seconds of mutual commiseration and admiration, and then move on).

New Wave Reprise

Of all the possible angles to take on the story, sitting in Esprit's modest offices on Spadina Ave, with Pauk tapping his fingers on the table for emphasis as he talks, Esprit's April 5 "New Wave Reprise," a one-off event at Trinity-St.Paul's Centre, cuts right to the heart of what makes Esprit, and its founding conductor, tick, so we start right there.

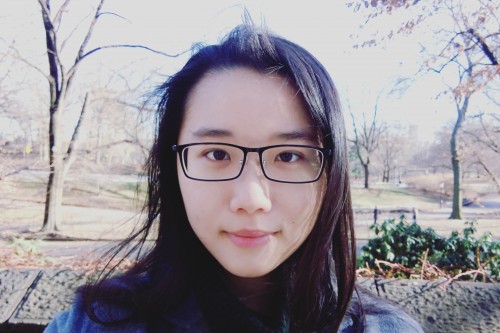

The Orchestra's own description of the event is fairly straightforward. It will start at 7pm with a keynote address by John Rea, and will feature world premieres by emerging Canadian composers (Eugene Astapov, Quinn Jacobs, Bekah Simms, Christina Volpini and Alison Yun-Fei Jiang). Eugene Astapov and Alison Yun-Fei Jiang (for one work) will also be the evening's guest conductors.

The Orchestra's own description of the event is fairly straightforward. It will start at 7pm with a keynote address by John Rea, and will feature world premieres by emerging Canadian composers (Eugene Astapov, Quinn Jacobs, Bekah Simms, Christina Volpini and Alison Yun-Fei Jiang). Eugene Astapov and Alison Yun-Fei Jiang (for one work) will also be the evening's guest conductors.

"What's the size of the ensemble for the event," I ask. "It's a much smaller group," Pauk replies. "Smaller winds, smaller strings, two percussion, harp, piano. So it's all the orchestral sounds. What's interesting is that these same composers, by and large, worked with us last year, for a slightly smaller group of instruments, and will, hopefully work with us again next year, at which time an even larger instrument group will be in play. It's not to treat them as unable to deal with the orchestra. It's to create a progression and maintain the relationship. It's something we have done from the beginning with all the generations of composers we have worked with."

He pauses, rummages for and reads from a piece of paper, a mission statement of some kind. This kind of sums it up," he says. "'The intent, from the beginning of Esprit, has always been to identify, engage, nurture, expose, promote and sustain relationships with creative people.' That's been it, basically, from the start of Esprit as a professional organization, of the orchestra, of the kind of outreach we've done. But, except perhaps with our musicians, nowhere more importantly than in our relationship to composers and composing. And you do that by repeatedly commissioning composers' work, and then reprising those commissioned works over the years. I mean if you trace the record over the years – John Rea, Chris Paul Harman, José Evangelista, Denis Gougeon, so many others. You seldom see their names just once. And we reach out constantly to new voices, and then bring them along, which is what this is about."

Astonishing as it may seem, Pauk can lay claim to five distinct generations of composers with whom Esprit has maintained this kind of relationship. "Harry Freedman and Harry Somers, along with Murray Schafer, were the senior generation. I was always influenced by those senior composers because they had strong, clear, independent and remarkable voices, and so that's what I've always looked for when I've programmed or commissioned.

Astonishing as it may seem, Pauk can lay claim to five distinct generations of composers with whom Esprit has maintained this kind of relationship. "Harry Freedman and Harry Somers, along with Murray Schafer, were the senior generation. I was always influenced by those senior composers because they had strong, clear, independent and remarkable voices, and so that's what I've always looked for when I've programmed or commissioned.

Then there is my own generation. Alexina [Louie], and John Rea are examples. And then there's the emerging generation represented by this event. And the next generation of high schoolers that this group of emerging composers will help bring along. Each benefitting from and contributing to the others in a kind of ongoing evolution."

"So why New Wave Reprise as a title?" I ask (and then almost wish I hadn't, because the New Wave Festival, launched in 2002 has gone through all kinds of twists and turns over the years). Watching me start to glaze at what begat what and when, Pauk suggests instead that I reach out to Eugene Astapov, who is an alumnus of several of Esprit's outreach programs, and features as one of the composers (and the main guest conductor) in the April 5 event.

Astapov's own journey with Esprit started over a decade ago when he participated, as a Grade 11 student, in composition workshops the orchestra hosted at Earl Haig Secondary School (site of Claude Watson School of the Arts), and is a case study in the kind of relationship building Pauk was talking about earlier. "I was fascinated to the extent that I decided to pursue it as a career, thanks to the support of a longtime Esprit friend and collaborator Alan Torok – director of the music program at Earl Haig at the time," Astapov says.

Astapov's own journey with Esprit started over a decade ago when he participated, as a Grade 11 student, in composition workshops the orchestra hosted at Earl Haig Secondary School (site of Claude Watson School of the Arts), and is a case study in the kind of relationship building Pauk was talking about earlier. "I was fascinated to the extent that I decided to pursue it as a career, thanks to the support of a longtime Esprit friend and collaborator Alan Torok – director of the music program at Earl Haig at the time," Astapov says.

A year later he began studying at the Eastman School of Music, but stayed in touch with Torok who subsequently re-introduced him to Pauk. As it happened, Esprit was engaged in preparations to host their annual New Wave Festival and commissioned Astapov for it. "It turned out to be a 12-minute work for piano and orchestra, only my second orchestral commission after the Vancouver Symphony. Thinking back now, even though the piece may not have been my strongest, I now realize how it fit like a puzzle with the subsequent works I composed and how the early experience with Esprit helped my understanding of the inner workings of a symphony orchestra."

After graduate studies at Juilliard, Astapov returned to Toronto for further studies at the doctoral level at the very point in time that Pauk and Esprit were reviving their collaboration with Earl Haig – what was eventually to become the educational outreach program known as Creative Sparks. "In 2015 I joined the community outreach team and was invited to return to Earl Haig as the composition instructor helping students compose new pieces for small orchestra, to be played by Esprit in concert at the end of the school year! As part of this project and example to the students at Earl Haig, Alex extended a commission to me to be performed at the Creative Sparks final concert."

Once again it was a pivotal commission, due to its use of a pre-recorded element – something he had not done before. "The piece was successful and was picked up by the Vancouver Symphony who performed it the following season," he says.

It's a continuing relationship at this point with ongoing opportunities for experimentation: music incorporating electronics; a Creative Sparks commission to compose a work for soprano and string orchestra; the opportunity to conduct that work; conducting unleashing a new passion. "It helped me open and alter my compositional mind and ears in ways that I had never realized was possible: deeper understanding of time signatures and tempi, orchestration techniques that help performers learn music quicker … The list goes on."

April 5 sees the latest installment in the Astapov/Esprit story. And it's highly likely it won't be the last. Which is something that wave after wave of other composers, senior, established, and emerging, can attest to.

John Rea, keynote speaker at the event, was the first composer Esprit ever commissioned. His working title for the address, Pauk informs me, is "Dialogue of the Wind and the Sea - Composers talking to Composers."

"In other words, making waves" says Pauk. And he should know.

David Perlman can be reached at publisher@thewholenote.com

Claude Vivier's Kopernikus a Hopeful Homecoming

Claude Vivier's opera Kopernikus was commissioned in 1978 by the University of Montreal's Music Faculty. Supported by the Canada Council, Vivier received a fee of $7,000 (approximately $22,000 in 2019 dollars), which allowed him to focus entirely on composition. Finished in May 1979, Vivier dedicated Kopernikus to "my maître and friend," Gilles Tremblay. Kopernikus was premiered a year later, on May 8, 1980 at the Théâtre du Monument National in Montreal.

Claude Vivier's opera Kopernikus was commissioned in 1978 by the University of Montreal's Music Faculty. Supported by the Canada Council, Vivier received a fee of $7,000 (approximately $22,000 in 2019 dollars), which allowed him to focus entirely on composition. Finished in May 1979, Vivier dedicated Kopernikus to "my maître and friend," Gilles Tremblay. Kopernikus was premiered a year later, on May 8, 1980 at the Théâtre du Monument National in Montreal.

Since its premiere Kopernikus has travelled extensively, making it the most restaged Canadian opera in Canadian history with over 55 performances. Ranking in second place is the opera Louis Riel (1967), with under 30 performances. However, whereas Louis Riel was performed only once outside of Canada, Kopernikus, mostly unknown at home, is highly celebrated in Europe with almost yearly performances. Canadian restagings have been sporadic: Montreal in 1986 by friends of Vivier via the Événements du neuf; Vancouver in 1990 via the Vancouver New Music Society; the large-scale tour de force of Thom Sokoloski and Autumn Leaf Performance that led to performances in several European and Canadian cities in 2000 and 2001; and the most recent iteration, a 2017 Banff Centre production coming to Toronto in April via Against the Grain Theatre.

"No one is a prophet in their own land" is a not unfamiliar expression in Canadian arts and, considering Vivier's profound relationship with religion and all things mystical, the expression is fitting; however, it is not much of an explanation for why Kopernikus is seldomly restaged here. In my search for answers I turned to the many Canadian articles and reviews about Kopernikus in the press over the past 20 years. Although producers and directors praise Kopernikus as a genius work of art, both the critics and the public generally express discontent over three recurring themes: the genre (the opera is not really an opera), the plot (there is no plot to follow, so how do you stage nothingness?), and its incomprehensible language (the opera is in French, German, and Vivier's own invented language).

Thinking back to my own experience with Kopernikus at the Toronto premiere in June 2001, I wish I had been better prepared to receive Vivier's work. When the performance ended, I was mesmerized, my head filled with complex sounds, syllables and meanings that took weeks to process. I also remember vividly the complete disconnect between various members of the audience; at the end of the performance the man sitting next to me was sleeping, but the one directly in front of me was on his feet madly clapping and hailing bravos at the performers. Since I have this wonderful opportunity to write about Kopernikus before the next set of performances, I hope I can not only help bridge that disconnect but also acknowledge and normalize the uneasiness that can come from it.

Pushing the boundaries

Pushing the boundaries

Although Vivier himself declared Kopernikus an opera, both seasoned critics and the public alike seem more comfortable with labelling it musical theatre (there are no arias) or oratorio (the theme is religious and the staging is minimal). Vivier, however, was insistent in calling this work an opera. In remarks prepared for the 1979 premiere, quoted here from Bob Gilmore's 2014 book, Claude Vivier: A Composer's Life, Vivier defends his categorization when he states that "opera, as a form of expression of the soul and of human history, cannot die. The human being will always need to represent his/her fantasies, dreams, fears, and hopes."In a later interview, with Angèle Dagenais in Le Devoir, March 3, 1980, when asked why he wrote an opera, a genre that is sometimes considered passé, he responded that "l'opéra permet la représentation d'états excessifs, et d'une dimension fantaisiste inconnue du théâtre."Clearly, Vivier did not conceive Kopernikus as either a work of musical theatre or as an oratorio.

Vivier does push the boundaries of the operatic genre but not, as some believe, as a rejection of the old masters. Vivier was an avowed fan of Mozart; Agni, the main character in Kopernikus, undertakes a journey not unlike the main characters in Mozart's Die Zauberflöte. This expansion of boundaries is simply a composer evolving into his own mature style, finding new ways to disrupt expectations, and creating new roles and sounds for melody. In fact, and this could be the topic of an entirely different article, the style of melodic writing that draws breath in Kopernikus ultimately serves as a stepping stone for several of Vivier's later works.

In scanning reviews, it also became apparent to me that part of Vivier's contextualization of Kopernikus in the score of the opera was misunderstood in translation. Vivier wrote: "Il n'y a pas à proprement parler d'histoire, mais une suite de scènes..." The first part, "il n'y a pas à proprement parler d'histoire" has been translated, interpreted, and served to the public as "there is no actual story," which is a mistranslation. 'À proprement dit' or 'à proprement parler' is one of those very common, and confusing, francophone expressions. Add a negative in front of it and a language barrier is erected. As a native Francophone, however, I understand that Vivier is saying that Kopernikus is not a story in the traditional sense, rather than that there is no narrative. Granted, Vivier's opera is devoid of villains or external conflict and this, perhaps, adds to the confusion. However, Agni, the central figure in Kopernikus undergoes a series of initiations that ultimately lead her to reach her final and purest spirit state, her dematerialization. The story is inherent in the series of scenes, in her ritualistic journey, where she encounters historical and mythical beings (her mother, Lewis Carroll, Mozart, the Queen of the Night, Tristan, Isolde and Copernicus) who accompany her from one world to the next.

Admittedly, the bare staging that typically accompanies Kopernikus can also be taken as a lack of narrative direction. It is, however, very much in line with Agni's journey towards the purest of spiritual forms. Vivier explicitly left behind paragraphs of texts explaining each scene of the opera so that creative staging decisions could be left to the directors. Perhaps an unusual choice, but an explanation can be found in Vivier's own words, again quoted from Gilmore's book, when he states that he loves many operas of the standard repertory but "I rarely go see them because I usually don't like the staging."

Although Vivier kept out of staging decisions, he very much injected traces of himself throughout the staging of Kopernikus: the opera is scored for seven singers and seven instrumentalists (the number seven makes several appearances in other works and Vivier's birthday is April 14); and in iconography Agni, the Hindu God of fire, is represented by a ram (Vivier's astrological sign is Aries, a fire sign).

Fascinated with languages (he could speak at least five fluently), Vivier is perhaps the only composer to use an invented language throughout his entire compositional career, beginning with his first vocal work, Ojikawa (1968), and ending with his last, Glaubst du an die Unsterblichkeit der Seele (1983). In Kopernikus, as in all of his previous works, his invented language is not a series of aleatoric nonsensical syllables, but rather a combination of automatic writing and the use of grammelot (coined by Commedia dell'arte players, grammelot refers to sounds, such as onomatopoeias, used to convey the sense of speech). Vivier's invented language also seems to function as a code for Agni who most often speaks in the invented language to other characters but speaks French when expressing her inner thoughts.

Kopernikus also shows early indications of spectralism, a musical practice where compositional decisions are often based on visual representations (spectrograms) of mathematical analysis of harmonic series. Vivier's spectralism of the late 1970s is an exploration of sounds as living objects and what he calls colours in both the sounds and textures he creates. Vivier's linguistic skills, combined with his strong predilection for vocal writing and his early foray into spectralism, elevate the opera to a stunning work of art where simple lines of music are turned into extraordinary meaningful moments that surpass any semantic value.

Looking ahead

Looking ahead

In one of his last letters, Vivier wrote to Montreal conductor Philippe Dourguin and laid out his outline for a second opera. His "opéra fleuve" on the explorer Marco Polo was to consist of seven parts and use previously composed materials. Conductor Reinbert de Leeuw (Asko/Schoenberg Ensemble) and director Pierre Audi (Nederlandse Opera) reconstituted Vivier's opera in the 1990s. Because their version was different than what Vivier originally lays out in his letter, the opera was renamed Opéra-fleuve en deux parties, with Kopernikus as part one and Rêves d'un Marco Polo as part two. Part two ends with Vivier's final composition, the very much discussed Glaubst du an die Unsterblichkeit der Seele (Do you believe in the soul's immortality). In 2000, as part of the Holland Festival, Vivier's Opéra-fleuve en deux parties received eight performances in Amsterdam, marking the world premiere of Rêves d'un Marco Polo. The production was subsequently revived, also in Amsterdam, in 2004, recorded by the Asko/Schoenberg Ensemble and released on DVD in 2006. Perhaps, we too, can soon have a premiere of Vivier's Opéra-fleuve en deux parties and discover Rêves d'un Marco Polo.

Until then, we have Against the Grain Theatre's Kopernikus to look forward to. Since the company's past productions have audaciously reinterpreted operas of the classical repertoire, it seems a natural fit for AtG to move towards shaking things up in the unexplored world of Canadian opera (there are over 300 Canadian operas to choose from!). In the company's press release, stage director Joel Ivany proclaims Kopernikus as "Canada's greatest opera ever written" and promises an "an epic journey of fire, life, death and ultimately, hope." His passion for the opera, and the stellar team that surrounds the production, does indeed give much to hope for: hope that Kopernikus receives the recognition it deserves and hope for a leading opera collective to guide us in towards a new era of (re)discovering our own Canadian works.

Kopernikus is not only a work of great vision and originality, it is also the legacy of a deeply spiritual and intellectual man. From life to death and timeless mystical spaces, the opera transports its listeners on a journey without the usual grounding semantic references. What then, is a listener to do? As Paula Citron reminds us, in her 2001 article on Kopernikus for Opera Canada, Vivier said it best on opening night in 1979: "... Let things go and just listen to the sound."

Against the Grain Theatre presents Claude Vivier's Kopernikus on April 4 to 6 and April 11 to 13 at Theatre Passe Muraille Mainspace.

Sophie Bisson is a PhD student in musicology at York University and an opera singer who is passionate about Canadian repertoire. Her doctoral research focuses on Canadian opera.

Musical Creation Through Community Engagement

Community-engaged arts practices have experienced tremendous exponential growth over the last few decades with many musical presenters taking on this mandate alongside their usual concert production activities. At the heart of this artistic practice is a dialogue between professional artists and community organizations with the outcome being a collective artistic expression. The process involved is considered as important as the final artistic result. In this month's column, I'll be looking at a cross-section of different community-based projects to give you a bird's-eye look at different community-focused events in March.

First though, a very preliminary view of an intriguing work in progress being co-produced by Soundstreams and Jumblies Theatre. Anishinaabe composer Melody McKiver has been commissioned by these two organizations to compose a work for string quartet and recorded voices.

First though, a very preliminary view of an intriguing work in progress being co-produced by Soundstreams and Jumblies Theatre. Anishinaabe composer Melody McKiver has been commissioned by these two organizations to compose a work for string quartet and recorded voices.

As synchronicity would have it, I was introduced to McKiver in a local restaurant, in early February, by Jumblies' artistic director Ruth Howard, just before Soundstreams presented a performance of Steve Reich's Different Trains, also a work for string quartet and pre-recorded tape. (My concert report of that evening can be viewed on The WholeNote website). Little did I realize at the time McKiver's upcoming connection to what we were about to hear that night.

Wanting to find out more about the project, I spoke recently on the phone with McKiver who was just ending a residency at the Banff Centre that brought together various Indigenous composers and performers. In our conversation, McKiver told me that Reich's music has been a major influence and inspiration, particularly while studying for an undergraduate degree in viola performance at York University where they spent endless hours listening to Different Trains –."at least 100 times," they said. The new commissioned work is titled Odaabaanag, which means trains or wagons in Ojibwe, and is their response to Different Trains, composed in 1988. They will be using Reich's methodology but looking at a different subject. Different Trains is Reich's reflection as a Jewish-American composer on the Holocaust which he, living in the USA during the war, did not personally experience. McKiver's work will also be for string quartet and recorded voices and will be McKiver's reflection as a young Anishinaabe composer who did not live through the residential school era, but lives with the impact of what happened.

In much the same way that Reich created his work from the speech rhythms of various interviews he conducted, McKiver will be interviewing Indigenous elders from their community—the Lac Seul First Nation—as well as others from Sioux Lookout in Northern Ontario, the home of a large Indigenous population. They will use excerpts from these recordings to form the melodic and rhythmic content of the work. Currently, McKiver is in the beginning stages of the compositional process, conducting the interviews and transcribing and reviewing the recordings to find those key phrases to use in the composition. The first elder they interviewed was Garnet Angeconeb, a well-known residential school advocate. I was shaken up when McKiver told me the story that Angeconeb spoke about in the interview. During the 1930s, the Lac Seul First Nation community was flooded causing the loss of their entire land base. The cause of this flooding was a hydro dam project which the community was not told of and almost overnight, up to 40 feet of water appeared, destroying people's homes and livelihoods. It was an apocalyptic moment, McIver said, that continues to have an ongoing impact on the community.

While Jumblies and Soundstreams are based in Toronto, McKiver has been given the opportunity and flexibility to work from their own land base. "This is so integral to being an Indigenous composer, to still live on my ancestral homelands and to be able to share this work." They'll be providing excerpts from the interview tapes as well as Skyping in to dialogue with Jumblies' community groups in Toronto. "There will be a long discussion process throughout the creation of the work," McKiver said. "People won't just be meeting the voices of my elders through the format of a string quartet, but the community will be able to listen to a 20-minute story rather than just a three-minute excerpt used in the string quartet. This way they can become acquainted with the stories and teachings that are being shared with me in multiple ways." Working with these stories has profound meaning for McKiver and navigating the transition point between the recorded stories and the string quartet form is challenging. McKiver seeks to "honour the stories that have been shared with me and this process is giving me a moment to deeply reflect on the teachings that I have been gifted. An important part of the process for me is to find a way where I can amplify these voices in a manner that is respectful." A work-in-progress performance is planned for May 2019 with the premiere performance scheduled for November 2019. Additional plans include a potential tour to Sioux Lookout as well as possible inclusion of interdisciplinary elements arising from the overall process. As well, there will be a companion choral piece composed by Melody's mother, Beverley McKiver, using the same themes and source material to be performed by the Gather Round Singers, Jumblies' mixed-ability, mixed-age community choir.

History of Bathurst Street Sounds

The History of Bathurst Street Sounds is another community-based partnership project, bringing together the Music Gallery, A Different Booklist, 918 Bathurst and Myseum of Toronto. On March 24, people can learn about the history of Bathurst Street soundscapes during a panel discussion and photo gallery launch at A Different Booklist to be followed by a parade to 918 Bathurst St. for an exhibition of Bathurst St. music archives. The history of music on Bathurst St. largely centres around various clubs, shops and the prominent Western Indian community historically located on Bathurst around Bloor. The extensive cluster of influential clubs in the Bathurst area included The Trane Studio, Lee's Palace, the Annex Wreckroom/Coda, and even Sneaky Dee's, originally located across from Honest Ed's. Clothing stores such as Too Black Guys helped supply the apparel for many golden-age hip-hop videos, and even Honest Ed's was once a destination for record buyers before its tenant Sonic Boom moved elsewhere. Various calypso mas ensembles were associated with spots in the area and the bookstore A Different Booklist has hosted a variety of Afrocentric cultural activities over the years. With all the changes happening in the neighbourhood and with the reconstruction of the Bloor/Bathurst intersection and much of Markham St, this event offers a rare opportunity to listen in to soundworlds both past and present.

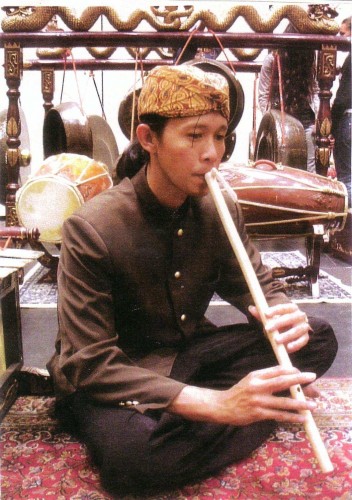

Evergreen Club Contemporary Gamelan

Gamelan music originates from Indonesia where its unique and complex sound textures have provided an essential and vital role in Indonesian community life with every town having its own gamelan and local musical traditions. The word gamelan refers to an orchestra of mainly percussion instruments crafted of metal arranged in rows on the floor including gongs hung from carved wooden racks. Other instruments include voice, a wind instrument called the suling and solo string-based instruments.

Canadian composer Colin McPhee (1900–1964) is well known for being the first Western composer to study the music of Bali and Java, and his associations, with American composers Henry Cowell and Lou Harrison for example, helped to usher in what became known as world music. Despite current sensitivities about cultural appropriation, this phenomenon of bringing non-Western influences into Western concert music has had far-reaching impact.

In 1983, composer Jon Siddall, with the assistance of Lou Harrison, established Canada's first ensemble performing on Indonesian gamelan instruments in Toronto – the Evergreen Club Contemporary Gamelan. The ECCG will be celebrating 35 years of commissioning, performing and recording contemporary music for gamelan with a concert on March 7 featuring music by master musician-composers Ade Suparman and Burhan Sukarma from West Java, Indonesia; Gilles Tremblay and Estelle Lemire from Quebec; as well as Peter Hatch and Bill Parsons from BC and Ontario. Playing on a grouping of instruments indigenous to West Java known as a gamelan degung playing in the Sundanese style, this pioneering Canadian ensemble has made a significant mark on the global gamelan scene and is committed to including Indonesian musicians and their music in their repertoire, as this concert demonstrates. One of ECCG's distinctive characteristics is the pursuit of a hybrid sound, combining gamelan, electroacoustics, minimalism, field recordings and elements of acoustic ecology, for example. Currently, they provide opportunities for the larger Toronto community to play their instruments at an ongoing meetup that happens on the second Sunday of the month at Arraymusic.

In 1983, composer Jon Siddall, with the assistance of Lou Harrison, established Canada's first ensemble performing on Indonesian gamelan instruments in Toronto – the Evergreen Club Contemporary Gamelan. The ECCG will be celebrating 35 years of commissioning, performing and recording contemporary music for gamelan with a concert on March 7 featuring music by master musician-composers Ade Suparman and Burhan Sukarma from West Java, Indonesia; Gilles Tremblay and Estelle Lemire from Quebec; as well as Peter Hatch and Bill Parsons from BC and Ontario. Playing on a grouping of instruments indigenous to West Java known as a gamelan degung playing in the Sundanese style, this pioneering Canadian ensemble has made a significant mark on the global gamelan scene and is committed to including Indonesian musicians and their music in their repertoire, as this concert demonstrates. One of ECCG's distinctive characteristics is the pursuit of a hybrid sound, combining gamelan, electroacoustics, minimalism, field recordings and elements of acoustic ecology, for example. Currently, they provide opportunities for the larger Toronto community to play their instruments at an ongoing meetup that happens on the second Sunday of the month at Arraymusic.

Barbara Croall

On March 31, a newly commissioned oratorio, Miziwe… (Everywhere… ), by Odawa First Nation composer and musician Barbara Croall, will be premiered by the Pax Christi Chorale and sung in Ojibwe Odawa with surtitles. In October 2018, I had the great honour of attending another one of Croall's premieres in Montreal – Saia'tatokénhti: Honouring Saint Kateri. I attended two performances of this work – the first at the Kahnawake Catholic Church located on Kahnawake Mohawk Territory, and the second at St. Jean Baptiste Church in Montreal. The music was performed by the McGill Chamber Orchestra, conducted by Boris Brott, who played a key role at various stages of the work's gestation, both in terms of his mentorship of Tara-Louise Montour, the work's solo violinist, and in suggesting that Croall consider composing the music for the project. The texts (by Darren Bonaparte) were spoken in Mohawk by a member of the Kahnawake community. The piece also included traditional Mohawk music sung by community members. The work told the story of Kateri Tekakwitha, a17th-century Mohawk young woman who converted to Catholicism after a traumatic exodus from her traditional homelands in upstate New York due to her villages being razed by fire. She ended up with the Jesuit mission on the south shore of the St. Lawrence River and was believed to have extraordinary healing abilities. She was eventually canonized as a saint.

To create that work, Croall spoke at length with elders from Kahnawake and Kanasatake, as well as elders in her own community, particularly about their Catholic faith and how they understand that in light of the church's treatment of Indigenous people in residential schools. In an interview she gave before the performance, she spoke about how these elders understand their Christian faith as being different from the European form, and in their mind they have transformed Catholicism into a matriarchal belief system, blending Mary with the traditional corn goddess.

In this latest commissioned work, Miziwe… (Everywhere…), Croall will be performing on cedar flute and voice along with Rod Nettagog, an Ojibwe (Makwa Dodem/Bear Clan) performer from the Henvey Inlet First Nation who also performed in Croall's orchestral work Midwewe'igan (Sound of the Drum). Other performers include Krisztina Szabó, mezzo soprano; Justin Welsh, baritone; and the Toronto Mozart Players. Croall has recently been appointed artist-in-residence and cultural consultant by the Kitchener-Waterloo Symphony.

IN WITH THE NEW QUICK PICKS

MAR 16, 8PM: Array Space, Arraymusic. The latest in the Rat-drifting series curated by Martin Arnold features artist and improviser Juliana Pivato. This performance will include various experiments on popular song.

MAR 19, 7:30PM: Canadian Music Centre. Pianist R. Andrew Lee performs Ann Southam's Soundings for New Piano.

MAR 24, 8PM: Esprit Orchestra's "Grand Slam!" concert features Trompe l'oeil, a world premiere by Canadian Christopher Thornborrow; Japanese composer Maki Ishii's Afro-Concerto; and Unsuk Chin's (Korea) Cello Concerto.

MAR 29, 8PM: Music Gallery. The latest concert in the Emergents Series with pianist Jana Luksts and the ensemble Happenstance who will present recital projects shaped around reimagining how classical music can sound, transforming the chamber music format into something new.

MAR 29, 8PM: Music Gallery. The latest concert in the Emergents Series with pianist Jana Luksts and the ensemble Happenstance who will present recital projects shaped around reimagining how classical music can sound, transforming the chamber music format into something new.

APR 5 7:30: Esprit Orchestra presents their New Wave Reprise Festival featuring world premieres by five emerging composers: Emblem by Eugene Astapov; Music about Music by Quinn Jacobs ; Foreverdark by Bekah Simms; as within, so without by Christina Volpini; and Temporal by Alison Yun-Fei Jiang. A keynote address by Montreal composer John Rea will round out the evening.

Wendalyn Bartley is a Toronto-based composer and electro-vocal sound artist. sounddreaming@gmail.com.

Chamber Cornucopia Makes for an Early Spring

On March 17, Christian Blackshaw, now 70, brings a selection of works from his acclaimed Complete Mozart Sonata Series, performed and recorded at London's Wigmore Hall, to Walter Hall. Hailed as "magical," "captivating," and "masterful," the fourth volume of the series was named as one of the Best Classical Recordings of 2015 by The New York Times. Blackshaw's all-Mozart program for Mooredale Concerts will include Sonata No.11 in A Major, K331 and Sonata No.14 in C Minor, K457.

On March 17, Christian Blackshaw, now 70, brings a selection of works from his acclaimed Complete Mozart Sonata Series, performed and recorded at London's Wigmore Hall, to Walter Hall. Hailed as "magical," "captivating," and "masterful," the fourth volume of the series was named as one of the Best Classical Recordings of 2015 by The New York Times. Blackshaw's all-Mozart program for Mooredale Concerts will include Sonata No.11 in A Major, K331 and Sonata No.14 in C Minor, K457.

In a 2013 interview with Gramophone after his year-long Wigmore Hall series, Blackshaw spoke of Mozart as a particular passion. "It was a sort of penny-dropping moment discovering Mozart," he said. '"I think I'm a frustrated singer and to me the sonatas can be construed as being mini-operas. I find his whole being informed by the voice and the vocal line." In the interview he rejected a characterization of Mozart's music as being "restrained." "There have got to be elements of joie de vivre," he responded. His own ultimate goal in performance is a state of "slow, calm release" where he can reach "a sense of communion." And does he find music more conducive to communion than words? "Yes," he said instantly. "There's no small talk [in music]."

COC Noon-hour Concerts

COC Noon-hour Concerts

Born in Siberia to a family of medical PhDs, Nuné Melik started playing the violin at the age of six; her first solo performance with orchestra took place a year later at the Kazan Symphony Hall. A prizewinner of numerous competitions and audience awards, she has performed across the globe, including the Stern Auditorium and Weill Recital Hall in Carnegie Hall and our own Glenn Gould Studio. In 2010, as an umbrella for her exploration of new repertoire, Melik founded the Hidden Treasure International Project, comprising research, performance and lectures of rarely heard music. By way of performances and lectures she also advocates for and promotes the music of the Caucasus, her heritage. Together with her longtime collaborator, pianist Michel-Alexandre Broekaert, in October 2017 she launched Hidden Treasure, a CD featuring unknown works by Armenian composers with Melik's own original program notes; CBC radio called it a "love letter to Armenia."

A multi-talented artist who speaks five languages, Melik produced and directed a documentary last year about Armenian composer Arno Babadjanian. She has published books of poetry in Russian, which were translated into Armenian by the Writer's Union of Armenia in 2016. Together with her CD, a book of French and English poetry was simultaneously released in October 2017.

COC presents Nuné Melik's "Hidden Treasures – Armenian music unearthed" on March 12, with collaborative pianist Michel-Alexandre Broekaert, a free concert in the Richard Bradshaw Amphitheatre of the Four Seasons Centre.

The Castalian String Quartet, founded in 2011 and based in London, England, was a finalist in the 2016 Banff Competition won by the Rolston String Quartet. Last year they were named the winner of the first Merito String Quartet Award/Valentin Erben Prize which includes €20,000 for professional development, along with a further €25,000 towards sound recordings and a commission. The award came as a complete surprise to the quartet since there was no application process or competition for it; instead a secret jury assembled a shortlist of five quartets which were then observed in at least two concerts during the course of a year, always without the musicians' knowledge.

The Castalian String Quartet, founded in 2011 and based in London, England, was a finalist in the 2016 Banff Competition won by the Rolston String Quartet. Last year they were named the winner of the first Merito String Quartet Award/Valentin Erben Prize which includes €20,000 for professional development, along with a further €25,000 towards sound recordings and a commission. The award came as a complete surprise to the quartet since there was no application process or competition for it; instead a secret jury assembled a shortlist of five quartets which were then observed in at least two concerts during the course of a year, always without the musicians' knowledge.

According to the award announcement, "The aspects that were evaluated included their professional approach, repertoire, programming, the artistic quality of the concerts, their musical profile, and also the imagination and innovation displayed by the musicians. Their artistic career to date and recordings, where applicable, were also evaluated."

The award is an initiative of Wolfgang Habermayer, owner of Merito Financial Solutions, and Valentin Erben, founding cellist of the Alban Berg Quartet. "The critical factor for us is how the young musicians behave in 'everyday life' on the concert stage," said award co-founder Erben. "The human warmth and aura radiated by these four young people played a key role. They are never just putting on a show – the music is always close to their heart. You can feel their intense passion for playing in a quartet."

The Castalian String Quartet performs in the Richard Bradshaw Amphitheatre of the Four Seasons Centre in a COC free noon-hour concert on April 4. The program includes Haydn's String Quartet Op.76, No.2 "Fifths" (a reflection of the Castalians' passion for the inventor of the string quartet), and Britten's String Quartet No.2, written just after WWII to mark the 250th anniversary of Henry Purcell's death.

Women's Musical Club of Toronto

Women's Musical Club of Toronto

Now in her mid-20s, Georgian pianist Mariam Batsashvili is another promising young artist. She began studying the piano at four; by seven, "completely in love with the instrument," she knew she wanted to be a pianist for the rest of her life. She gained international recognition at the tenth Franz Liszt Piano Competition in Utrecht in 2014, where she won First Prize as well as the Junior Jury Award and the Press Prize. This success led to performances with leading symphony orchestras, and to an extensive program of recitals in more than 30 countries. She was nominated by the European Concert Hall Organisation (ECHO) as Rising Star for the 2016/17 season. A BBC Radio 3 New Generation Artist, she is performing at major festivals and concert venues across the UK as part of that award.

Her comprehensive April 4 recital in the Music in the Afternoon series of the Women's Musical Club of Toronto begins with Busoni's soaring arrangement of Bach's iconic Chaconne from Partita No. 2 for violin, BWV 1004, taps into Schubert's fountain of lyricism, the Impromptu Op.142, No.1 D935, moves on to Mozart's haunting Rondo in A Minor, K511 and Liszt's virtuosic Hungarian Rhapsody No.12; then concludes with Beethoven's notoriously difficult Sonata No.29 in B-flat Major, Op.106 "Hammerklavier." In Walter Hall; just a few weeks after a performance in London's Wigmore Hall.

Kitchener-Waterloo Chamber Music Society

Janina Fialkowska's March 11 recital for the Kitchener-Waterloo Chamber Music Society, marking her 37th year of performing for KWCMS, features an ambitious, well-packed program that begins with Mozart's beloved Sonata in A Major, K310. An impromptu by Germaine Tailleferre; a nocturne by Fauré; an intermezzo by Poulenc; two pieces by Debussy; and Ravel's Sonatine – a selection of music by French composers, reminiscent of a French program by Fialkowska's teacher, Arthur Rubinstein – lead into three mazurkas, a nocturne (Op.55, No.2), scherzo (No.3) and ballade (No.4) by Chopin (the composer with whom she is most identified) performed in Fialkowska's inimitable style.

Later in the month, clarinetist James Campbell joins the Penderecki String Quartet for Brahms' splendid Clarinet Quintet. Dvořák's Quartet No.10 in E-flat Major, Op.51, "Slavonic" is the other major work on the March 20 program.

Timothy Steeves steps away from his usual role as pianist with Duo Concertante for a recital of four adventurous Haydn sonatas on April 1, his second all-Haydn recital for the KWCMS.

Music Toronto

Danny Driver's March 5 recital was the subject of my conversation in our February issue with the Hyperion Records artist, who "may be the best pianist you've never heard." Works by CPE Bach, Schumann, Saariaho, Ravel and Madtner will be performed by this uncompromising artist who demands a lot of himself: "When I feel I have come close [to achieving what I set out to achieve artistically], it's an intensely rewarding experience."

The following week on March 14, the Lafayette String Quartet – artists-in-residence at the University of Victoria since 1991 – who have spent more than 30 years together with no changes in personnel – partners with the Saguenay (formed in 1989 as the Alcan) String Quartet to perform three string octets. Join them in this rare opportunity to hear Niels Gade's String Octet in F Major, Op.17, Russian-Canadian Airat Ichmouratov's String Octet in G Minor, Op.56, "The Letter" and Mendelssohn's deservedly famous Octet in E-flat Major, Op.20.

The Saguenay String Quartet) and the Lafayette have played together many times, a reflection of their special musical bond and creative friendship.

CLASSICAL AND BEYOND QUICK PICKS

MAR 8, 8PM AND 9, 2:30 & 8PM: Critically acclaimed violinist Nikki Chooi is the soloist in Vivaldi's indispensable The Four Seasons with the Kitchener-Waterloo Symphony. Nicolas Ellis, who was recently named artistic partner to Yannick Nézet-Séguin and the Orchestre Métropolitain for the 2018/19 and 2019/20 seasons, leads the KWS in Beethoven's essential Symphony No.6 "Pastoral."

MAR 9, 7:30 AND 10, 3PM: Gemma New leads the Toronto Symphony Orchestra in Shostakovich's kinetic Symphony No.5; Kelly Zimba, flute, and Heidi Van Hoesen Gorton, harp, take charge of Mozart's Concerto for Flute and Harp K299/297c, the first work Mozart ever wrote for that combination of soloists.

MAR 9, 7:30 AND 10, 3PM: Gemma New leads the Toronto Symphony Orchestra in Shostakovich's kinetic Symphony No.5; Kelly Zimba, flute, and Heidi Van Hoesen Gorton, harp, take charge of Mozart's Concerto for Flute and Harp K299/297c, the first work Mozart ever wrote for that combination of soloists.

MAR 10, 2:30PM: Bradley Thachuk leads the Niagara Symphony Orchestra and TSO concertmaster Jonathan Crow in Sibelius' richly Romantic Violin Concerto Op.47. Sibelius' satisfying Symphony No.3 completes the nod to the great Finnish composer.

MAR 16, 7:30PM: Gemma New conducts the Hamilton Philharmonic Orchestra in a heavenly program featuring Debussy's hypnotic Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun and his impressionistic Nocturnes. Holst's riveting The Planets completes the exciting evening.

MAR 20, 2:30PM: Georgian Music brings the Lafayette and Saguenay String Quartets to Barrie for a repeat of their Music Toronto program of March 14 headed by Mendelssohn's youthful masterwork, his Octet in E-flat Major, Op.20.

MAR 23, 7:30PM: Barrie Concerts presents the Penderecki String Quartet in an evening of Dvořák's chamber music. Included are the composer's String Quartet No.10 "Slavonic" and, aided by pianist Benjamin Smith, both of his piano quintets, the second of which (Op.81) is one of the masterpieces of the form.

MAR 23, 7:30PM: The Oakville Chamber Orchestra celebrates their 35th anniversary with a performance of Bach's Six Brandenburg Concertos, an invigorating choice of music for such an auspicious occasion.

MAR 27 AND 28, 8PM: Gunther Herbig, TSO music director from 1989 to 1994, conducts two pillars of the 19th-century repertoire: Schubert's movingSymphony No. 8 "Unfinished" and Bruckner's Symphony No.9, the fourth movement of which the composer left unfinished on the day he died, leaving only the first three movements complete.

MAR 30, 7PM: Mandle Cheung continues to realize his conducting dream, leading his orchestra in Tchaikovsky's Piano Concerto No.1 (Kevin Ahfat is the soloist) and Mahler's titanic Symphony No.1.

MAR 30, 8PM: The Canadian Sinfonietta, with guest violist Rivka Golani, mark the onset of spring with the world premiere of David Jaeger's Raven Concerto for viola and chamber orchestra, Copland's lovely Appalachian Spring, Britten's Lachrymae Op.48a for viola and strings and Elgar's Serenade for Strings. Tak Ng Lai conducts.

MAR 30, 8PM AND 31, 2PM: The Oakville Symphony celebrates the musical friendship between Brahms (Symphony No.2) and Dvořák (Violin Concerto). Leslie Ashworth is the violin soloist; Robert De Clara, music director since 1997, conducts.

APR 7, 1PM: Gramophone magazine called American-born Marina Piccinini "the Heifetz of the flute." Find out why at the RCM free (ticket required) concert at Mazzoleni Hall; with Benjamin Smith, piano.

APR 7, 3PM: RCM presents the justly celebrated American pianist Richard Goode in an all-Beethoven recital that includes the "Pastoral," "Moonlight" and "Les adieux" sonatas, and selections from the Op.119 Bagatelles, all topped off by the master's final sonata, the celestial Op.111.

Paul Ennis is the managing editor of The WholeNote.

So You Think You Can Dance Laura Roderman

Source: https://www.thewholenote.com/index.php/newsroom/blog/music-and-the-movies/522-newsroom?limit=5&start=280

0 Response to "So You Think You Can Dance Laura Roderman"

Post a Comment